2.04 UGANDA: Possibly the best place to be a refugee in the world

Climate change is anticipated to displace anywhere between 25 million and 1 billion people worldwide by 2050. Learn how developing nations like Uganda host the majority of the worlds refugees and how their generosity is something for the rest of the world to aspire to.

Community dialogue meeting between the refugees and the host community, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru (2017)

The country of Uganda currently hosts over 1.6 million refugees from as many as 10 countries, with the largest numbers fleeing from South Sudan, The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Burundi, Rwanda and Somalia. Between 2016-2017 at the height of the European migration crisis, Uganda accepted more refugees than any other nation and now has one of the largest refugee populations in the world, even though it is itself a least developed country (LDC) with a history of conflict.

Meeting of Amuru’s core implementation partners to discuss the proceedings of, and requirements for world peace day at Maaji III Refugee Settlement, UNHCR Adjumani / Pakelle, Field Office, Pakelle, Amuru (2017)

Due to its liberal refugee policy that facilitates free movement, allocation of land, the ability to work and start a business, access to medical treatment and education, a culture of reciprocal migration between its neighbouring countries and the kinship of those that belong to ethnic groups who straddle international boarders, Uganda is arguably one of the best places to be a refugee in the world.

Issac Ijjo of Jesuit refugee Services Uganda, UNHCR Adjumani / Pakelle, Field Office, Pakelle, Amuru (2017)

However, without continuing support from the international community, the Northern and Eastern regions of Uganda that host the majority of the nation's refugees, both of which have a very recent history of conflict and are the most impoverished in the country, could themselves destabilise.

The South Sudanese Civil War began in 2013 when President Salva Kiir accused his former deputy Riek Machar of attempting a coup d’état. Machar, having denied trying to start a coup fled to lead the Sudan People's Liberation Movement In Opposition (SPLM-IO). Fighting soon broke out between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) lead by Salva Kiir and the SPLM-IO lead by Riek Machar.

South Sudanese Pounds, Pagarinya Refugee Settlement,, Amuru (2017)

The political conflict was further compounded by a prolonged climate exacerbated drought that had increased competition between communities along ethnic lines over dwindling water, food and grazing resources, leading unoccupied and frustrated men to be lured into the fight. As a result of the conflict and ensuing famine more than 2 million people were displaced from South Sudan to neighbouring countries with Uganda hosting the lions share of refugees at 1.1 million registered arrivals.

UN-OCHA map of South Sudan, UNHCR Elegu Reception Centre, Elegu / Nimule Border, Amuru (2017)

Those arriving in Uganda to seek asylum would first be received at collection points on the border between South Sudan and Uganda. At the peak of the conflict in July 2016 between 2-6,000 people were arriving everyday at Elegu collection point in the Amuru, the majority of which were women and children.

The belongings of newly arrived refugees, UNHCR Elegu Reception Centre, Elegu / Nimule Border, Amuru (2017)

When they first arrive, refugees give their family names and the size of their h to staff at the reception centre. As they wait for initial registration, refugees are given high energy biscuits, which for some may be the first thing they have eaten in days, with many refugees having walked for up to 10 days with only the clothes on their backs to reach Uganda. When they have initial registered gees are then given plastic wrist bands to indicate their status: a red band they require assistance, yellow if they are an unaccompanied child and blue for everyone else.

Newly arrived refugees, or new arrivals as they are referred to by the centres team, are then screened for malnutrition and vaccinated against Polio (children 0 - 5 years), Measles (children 6 months - 14 years) and Tetanus (Women). Where possible children are also de-wormed to improve their immunity.

Following their medical screening new arrivals are then transferred to a reception centre via bus or truck where they will be registered. This group of new arrivals is being transferred to Imvepi Reception Centre in Arua District. Before departing refugees are given more high energy biscuits and water for the journey.

Once at Imvepi Reception Centre, new arrivals must wait for registration during which each refugee will have their name, age, former residence, finger prints and photographs logged into an online registration system. Once the process is complete a ration card is issued to each household.

Temporary accommodation at Imvepi Reception Centre, UNHCR Imvepi Reception Centre, Arua District (2017)

Waiting for registration, UNHCR Imvepi Reception Centre, Arua District (2017)

Due to the process being dependant on an unreliable satellite internet up-link, new arrivals typically waited 14 days for registration and some as much as 22 days as connectivity issues caused massive delays. For those queuing, that means waiting up to eight hours a day in hot and crowded tents seated on hard wooden benches.

As they await registration new arrivals are given two meals a day, one of corn-soy blend (CSB) porridge in the morning and one of posho (maize flour porridge) and kidney beans in the afternoon. Although refugees were receiving all of their meals, many highlighted that cooking staff often ran out of porridge and then had to quickly cook more which meant that they were often served undercooked, which caused refugees stomach pain. At other times when beans were low, those waiting at Imvepi said, cooks would add cold water to the pot to bulk out the portions which left them hungry.

Waiting for hot food, UNHCR Imvepi Reception Centre, Arua District (2017)

Whilst waiting, refugees sleep in segregated temporary communal shelters, share pit latrines and have access to water for washing themselves and their clothes. Whatever belongings or livestock that they had brought with them would also kept in the shelters by refugees to stop them from being stolen. With only basic communal wash facilities and often only one change of clothes the extended wait for registration was compounding the suffering and trauma of new arrivals.

Having undergone a security check for weapons and ammunition at the collection centre, refugees are monitored by security supervisors due to concern that violence between the two principal ethnic groups aligned with the warring parties, the Dinka who are aligned with Salva Kiir’s government forces (SPLM) and the Nuer who are aligned with Riek Machar’s SPLM-IO could continue. Security is also in place to dissuade those who wish to abuse the system by registering as refugees multiple times. Known as “Recyclers”, those who attempt to re-register do so to profit from the sale of rations, core relief items and ration cards, if caught they risk being beaten before being deported back to South Sudan.

Clothes drying on a razor wire fence, UNHCR Imvepi Reception Centre, Arua District (2017)

Although the reception centres and collection point’s lie within secure fenced compounds and refugees are not able to leave until they are registered, at which point they will be transferred to the refugee settlement where they will live, there is no other time when refugees are held behind barbed wire in Uganda.

Children behind a razor wire fence, UNHCR Imvepi Reception Centre, Arua District (2017)

Once registration is finally completed, most new arrivals are then transferred by truck along with their belongings and livestock to a refugee settlement where they would spend another night in temporary accommodation before being allocated a plot of land. Only those that had proven that they had the financial capabilities to support themselves would be allowed to travel independently to the city of their choice where they would receive no further support.

In the morning, after another night in communal accommodation and a breakfast of beans and posho, refugees are transported into the bush to a section of the refugee settlement where there are unallocated plots of land.

Truck transportation to plots, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

The plots, each of which are a fifty square meter tract of unmanaged bush are allocated per household. With the settlement divided into blocks of plots which are demarcated by graded dirt tracks, individual plots are never more than several hundred metres walk from a water point. While those requiring assistance receiving plots with shelters and latrines already erected on them, all other new arrivals must build their own.

Once a plot is allocated a knot will be tied in the grass at each of its four corners to show that it has been claimed.

Once plots have been allocated, lunch is served in the bush and a number of core relief items (CRIs) are distributed. CRIs include: mosquito nets, sleeping mats, blankets, kitchen sets, sanitary towels, basins, jerry cans, solar lamps, wooden poles and when possible hoes and slashers. However, due to gaps in funding it is often the case that not all core relief items are received. In September 2017, Omugo refugee settlement was suffering from a shortage of solar lamps, which was making it difficult for new arrivals, such as PSN’s, especially those needing assistance, who needed to go to the toilet at night and mothers with young babies who needed to breast feed and change babies at night. The lack of solar lamps was also reducing the security of new arrivals by making them easier targets for thieves at night.

New arrivals waiting the distribution of Core Relief Items, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

Distribution of Core Relief Items, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

Once they have received their CRIs new arrivals must then build the shelter in which they will sleep until they can build a more permanent structure. To do so cutting tools like pangas and slashers are temporarily distributed by humanitarian staff who remain on site to demonstrate how to build a shelter. In the late afternoon, new arrivals also receive their first month's rations. from which they are expected to feed themselves until the next ration distribution.

New arrivals and their temporary shelter, Village 2, Tank 16, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

To establish more substantial accommodation, refugees are encouraged to clear their plots and source building materials from the bush such as grass, wood and if it is available stone. When out in the bush refugees faced the risk of scorpion sting and snake bite, particularly when cutting grass. In September 2017, at Omugo refugee settlement, a woman refugee had died having been bitten by a snake when cutting grass for her roof near to the settlements church. When building with poles, any nails that were required needed to be brought from the market by refugees, with few able to afford to spend what little cash they had brought with them to Uganda, the use of torn up mosquito nets as string to replace nails was common. As a result, those that had been forced to use their mosquito nets for building had little or no protection against malaria and dengue fever.

Hut under construction, village 2 tank 16 Omugo Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

_______, village 2 tank 16 Omugo Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

For those that were suffering from illness, that were on their own, were single mothers or were considered people with special needs (PSNs), being left alone on a plot, in what felt like the middle of the bush was a daunting prospect. However, those that had already established themselves in the refugee settlement often helped new arrivals to overcome the challenges of establishing themselves by helping them to clear plots, dig latrines, fetch water and look after their children as they settle in.

Hole being dug for a pit latrine, Village 2, Tank 16, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

For new arrivals like ______, the support of the newly establish community was invaluable. Having lost his leg when he was shot by government forces who were raiding his village for food supplies, ______ relies on neighbours to fetch water because he cannot maintain his balance when carrying a full jerry can. However, even-though ______ was unable to undertake most tasks that involve heavy lifting, he was helping his neighbour, who had recently undergone surgery for and appendicitis, to clear the grass on her plot.

_______ a family size one PSN, working to clear his plot, Village 2, Tank 16, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

Having been referred from Imvepi Reception Centre to Arua hospital to have an emergency appendicitis, ____ had received strict instructions from Medicine Sans Frontier (MSF) to avoid heavy foods like posho and beans for the next 3 weeks. even-though ____ had been given 20,000UGX (£4.15) to buy rice to eat for those 3 weeks, she had spent most of it on liquid foods whilst waiting to be registered at Impevi Reception Centre because she could not eat the meals of posho and beans that were served there. Although ____ was recovering well from the surgery, her mattress had been stolen from the Imvepi Reception Centre whilst she was in hospital, leaving her to sleep on the hard ground. However, now that she was in Omogo, ____ was receiving help from those that lived around her and she had recently been brought rice by Joseph, the leader of The Refugee Welfare Council in her block, to supplement her rations.

______ who has just returned from surgery and her child ______, Village 2, Tank 16, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

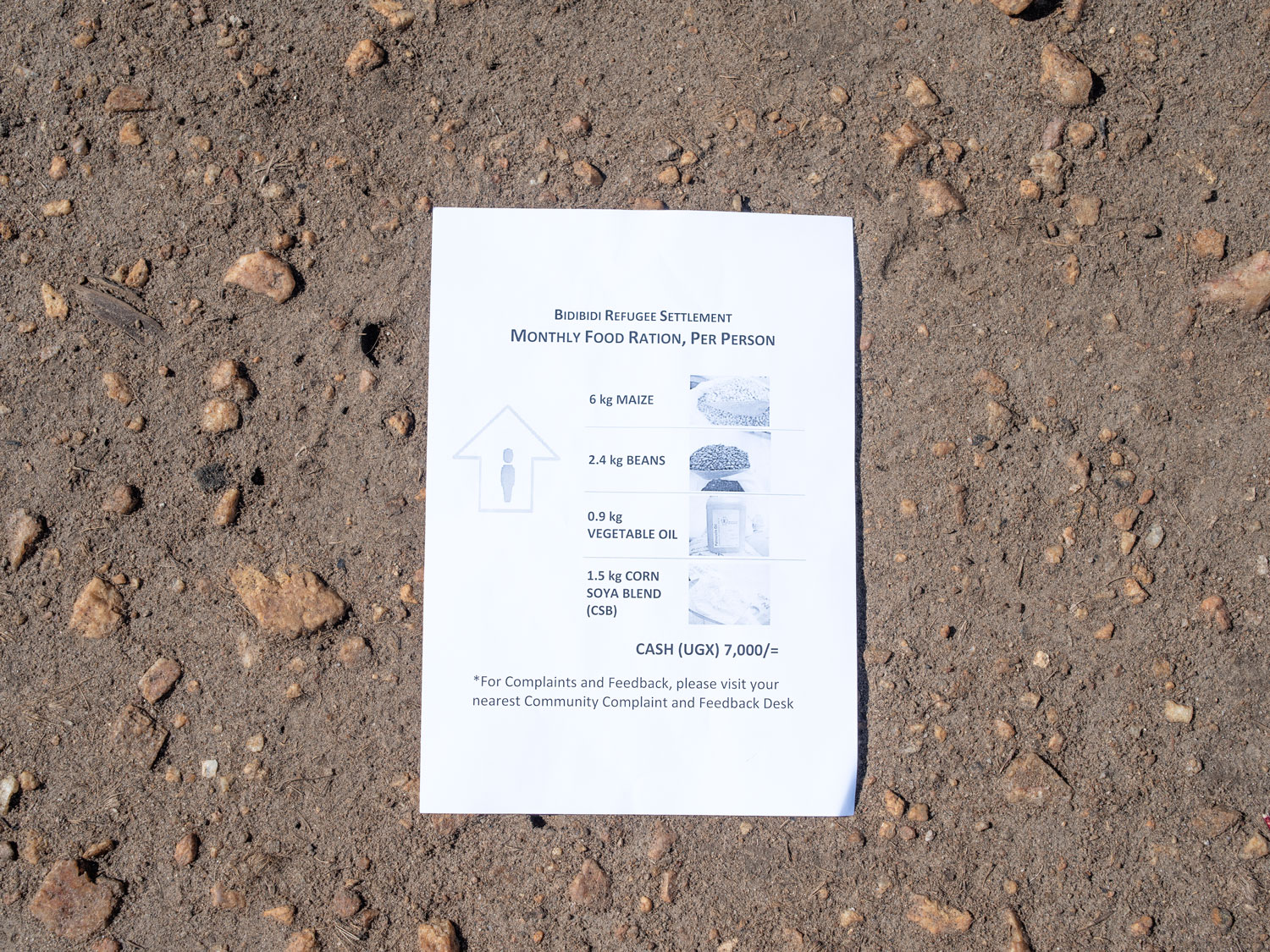

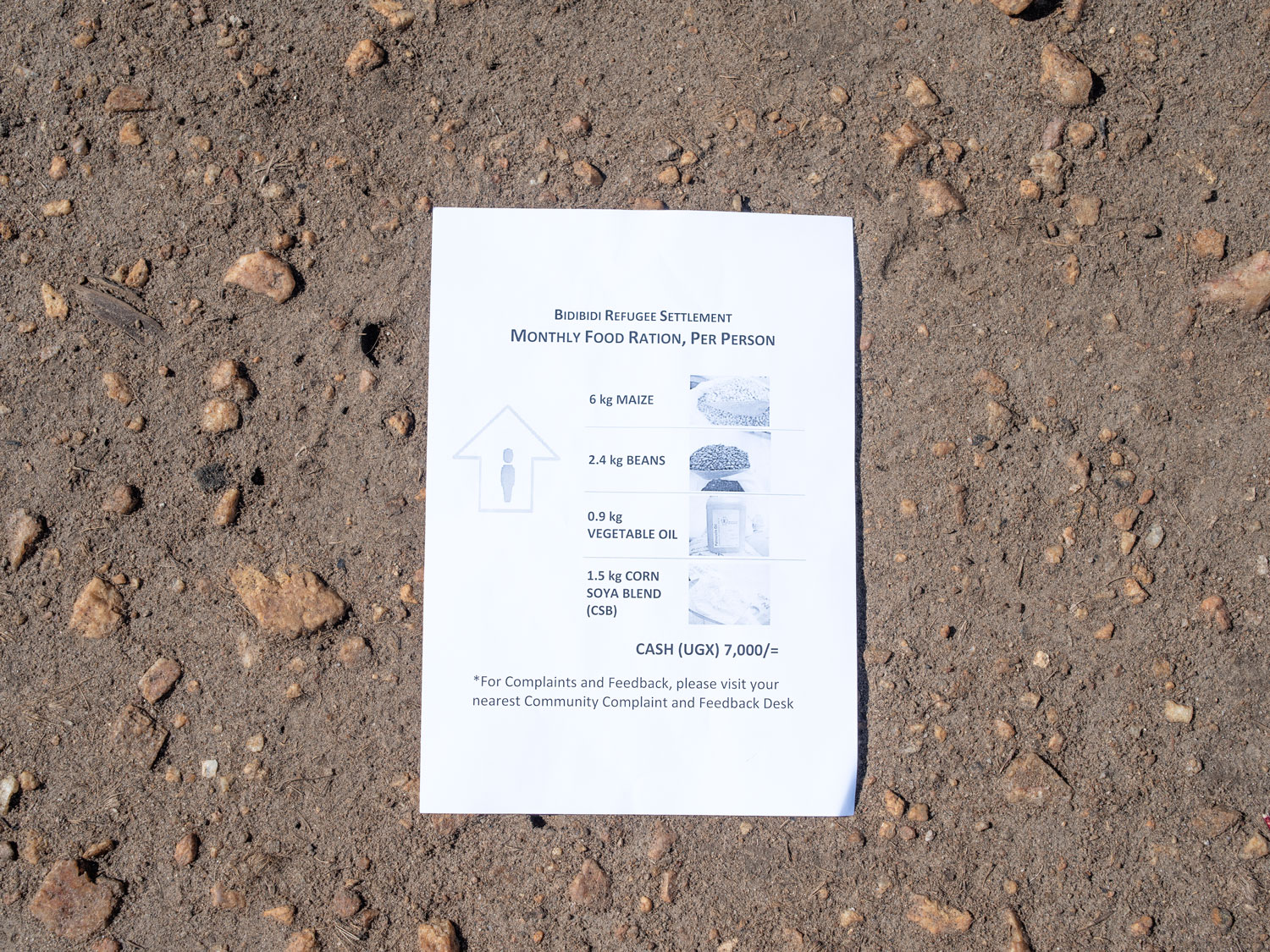

After receiving their first month's rations on the day of their arrival at their newly allocated plots, from then on refugees would receive their rations at the settlements distribution point once a month. Having presented a ration card, each household would receive 12kg of maize, 2.4kg of beans, 0.9kg of vegetable oil, and 1.5kg of corn soya blend (CSB), per documented family member each month.

September’s ration distribution, Zone 2, village 8, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

The PSN line, September’s ration distribution, Zone 2, village 8, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

In order to receive their rations, a representative of each household must queue up in one of ten lines, with each line representing the number of family members in a household from family size 1 to 10+. The 10 family sizes are then allocated their rations in bulk in groups of 10. When they have received their rations, each group of 10 is then tasked with equally dividing each of the food stuffs between themselves into the containers that they have brought with them. While able body refugees must sometimes wait several hours for their rations, PSN’s (people with special needs) queue separately and receive their rations before the family size groups.

But in September 2017, as funding from the international community dwindled, the maize ration was reduced from 12kg to 6kg, due to the cost of transporting the heavy grain.

Monthly ration, per person, ration distribution, Zone 2, village 8, Bidi Bidi, Yumbe District (2017)

Although rations were supplemented with 7,000UGX (£1.37 GBP) per person, households were concerned that the money was an insufficient amount to replace the missing maize, which was an essential barter commodity needed to gain access to the bush and to have the 6 remain kilos of the grain ground into flour. Women raised particular concern that the money would lead to increased alcoholism and child neglect, as men in some households were immediately spending all of the money on alcohol, usually cheep Cock brand gin that came in plastic packets, and thereby were leaving their families without sufficient food for the rest of the month.

Being denied rations due to lost ration cards or administrative errors, was the single biggest push factor that saw many refugees risk returning to S.Sudan and in some cases rejoining the conflict, which they deemed preferable to going without food in Uganda's refugee settlements.

PostBank kiosk and security guards, ration distribution, Zone 2, village 8, Bidi Bidi, Yumbe District (2017)

Although the infrastructure that supports Uganda's refugee settlements is administered by the Office of the Prime Minster (OPM) and managed by the relief agencies that have responded to the emergency, the settlement is also governed by a refugee welfare council (RWC), made of elected representatives from each block of plots.

Pagarinya Seventh Day Adventist church built by refugees on rented land, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru (2017)

Each RWC is tasked with setting up water management and market committee and a security council to protect the community and report crimes. Additionally, the RWC is responsible for deciding which relief agency lead interventions, journalists, or researchers the community wished to accept, and for voicing the concerns of the community to the settlements core implementation partners (the relief agencies that carry out regular work in their settlement). Each RWC will also facilitate conflict resolution meetings to mediate between the host population and refugees and disgruntled refugee parties. In this case a meeting was being held between refugees and the host population to discuss the rental of the plot of land on which the Seventh Day Adventist church at Pagarinya Refugee Settlement stood.

Community dialogue meeting between the refugees and the host community, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru (2017)

The meeting, which was held in the church, concluded successfully. As a result, the local land owners gifted the plot to the members of the church in appreciation of the refugee community's frequent rental of other land for agriculture use and in the knowledge that one day, the church would be returned to the host community when the refugees eventually returned to South Sudan. The dialogue’s success had also been enhanced by the fact that both the host's and refugee's belonged to the same ethnic group: The Madi Tribe. The Madi people, who lived in Pageri County in South Sudan, like those who resided in the districts of Adjumani and Moyo in Uganda, the regions that hosted the majority of Uganda’s South Sudanese refugees, had themselves on numerous occasions graciously received Uganda refugees. Most recently, in the 1980's and 1990’s, South Sudan had received Ugandan refugees when approximately half a million people had fled from the the fallout of the Ugandan Bush War and latterly Joseph Kony's Lords Resistance Army (LRA) which rose up out of the conflict.

The Chairman of the market comity (Centre left), his assistant (left) and members of the church (right of centre) discuss the land on which the church sits with it's owners (centre right). Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru (2017)

The renting of land had been made possible at Pagarinya Refugee Settlement through a high quality of dialogue between refugees and the host community. Although host communities in Adjumani and Moyo district were open to dialogue, those in Arua and Yumbe District were less so, owing to tensions between the impoverished host community and refugee population, as competition for resources such as fire wood and water sparked conflict. The West Nile region of northern Uganda is one of the most disadvantaged areas in the whole country. Following the Ugandan Bush War, during which much of the regions population faced persecution by rebel groups including the National Resistance Army (NRA), the leader of which, Yoweri Museveni, has been the autocratic leader of Uganda since 1986. Far from Kampala and stigmatised by it's history of conflict, the region faces marginalisation from the rest of the country.

For safe drinking water, refugees must fill their jerry cans up at a water point and then carry the water back to their plots. The water points, which can be tanks, solar-powered ground water pumps or hand pumped bore holes, are always in demand leading to long queues of jerry cans waiting to be filled up.

Hand pumped bore hole, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

_____ fetching water from a bore hole, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

According to the head of the water management committee of block 5 in Palorinya Refugee Settlement, the average amount of water used for domestic purposes by a family of 6 was eleven 20 litre jerry cans per day (approximately 220 litres). Of this water, 1 jerry can was used for cooking, 4 for clothes washing, 4 for showering, and 2 for drinking. On a day when a family did not wash clothes, they would use only 7 jerry cans (140 litres). For agricultural use the amount varied dramatically depending on what type of crop was being grown. According to Christo, from the RWC of Zone 2 in Palorinya Refugee Settlement, a 10x10m water thirsty eggplant bed would need between four or five jerry cans of water (80-100 litres) per day during the dry season.

_____, retuning from a bore hole with water, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

_____ fetching water from a bore hole, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

With water shortages often being caused by tanker delays and overcast days when solar pumps did not work, refugees would have to walk to water points further away where queues would become even longer than normal as a larger number of households depended on fewer water points. The water-point for village five and eleven in zone 2 of Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement had been without water for 3 weeks due to the access track leading to the water tower that fed it becoming inaccessible to water tankers. The track was only made passable again when women from the two villages water management committees took it upon themselves to haul and break rocks to repair the track.

With up to 400 households dependent upon one water point, long queues of jerry cans form early in the morning, often long before solar pumps are operational or water has been delivered to a tank.

It took some new arrivals as long as 5 months to build a permanent shelter, even though it often took as little as 3 days to build the structure.

The Security Secretary of the Refugee Welfare Councils house, Zone 1 Village 4, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

With competition for resources exaggerated by an influx of 272 thousand refugees to Yumbe district, a number that had doubled the population of the district in less than a year, Ugandan nationals who them-selves depended on the bush surrounding Bidi Bidi for survival, had attacked, raped, and killed refugees who had tried to collect building materials from the bush without paying or bartering for them.

The development of Zone 2, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District, Image © 2020 Maxar Technologies and CNS (2016 / 2019)

With as many as 52 poles needed to construct the walls of a hut and 18-20 bundles of grass needed to roof it, each costing between 1000-4000UGX ($0.54-1.07 USD). The members of the Refugee Welfare council of village 4, zone 1 in Bidi Bidi suggested that better dialogue with the nationals or an early injection of money for building materials would shorten the waiting time to build and stop refugees from returning to South Sudan.

Abandoned shelter, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo District (2017)

Once established refugees were expected to cultivate their land to supplement their rations and generate an income. With lean seasons in East Africa determined by rainy and dry seasons, refugees would prepare for the dry season by sun drying preserves of okra, eggplant, pumpkin, bean leaf, pumpkin leaf, cassava leaf and a variety of leaves from the forest.

Dried bean leaves, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo District (2017)

However, with rainy and dry seasons becoming increasingly erratic in East Africa, both local and refugee farmers faced greater food insecurity as too much rain damaged or waterlogged crops and dry-spells came at unexpected times or lasted longer than before.

_____ and her sorghum crop, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

Although there are medical centres serving each settlement the care can be provided is limited to the dispensing of medications like antibiotics and antimalarials, maternity and antenatal care and treatments for malnutrition. For surgical procedures refugees are referred to nearby hospitals which makes treatment inaccessible to some. Copas Kwaje, a resident of Bidi Bidi, explained that even though he had been diagnosed with bowel cancer and referred to a hospital in Arua, he believed he would be unable to attend the surgery because he had no money to pay for the journey to Arua, if transport was not going to be provided, or to feed himself while recuperating in the hospital.

Copas Kwaje, Village 8, Zone 2, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

Wani James had been shot in the leg whilst trying to escape fighting in his village. The injury still caused him a great deal of pain which was being exacerbated by having to sleep on a matt on the hard ground. As a PSN, Mr James should have been allocated a shelter and latrine upon his arrival to Bidi Bidi but he had not due to a lack of resources. He was therefore dependent on his daughter in law, who on her own had construct a shelter for herself, Mr. James and her infant daughter.

Wani James, Opposite Alaba Primary School, Village 8, Zone 2, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

Wani James, Opposite Alaba Primary School, Village 8, Zone 2, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

In the Dawut household, which is made up of 12 people and headed by Elisabeth, whose husband had recently passed away, there are 3 PSN’s, all of whom are elderly. Of the Dawut families PSN's, one has tuberculosis and another has Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Elizabeth described the two greatest challenges that the family faced. The first, that the family was having to sell rations to pay for diabetes medication following shortages at the health centre. And the second, which was the impossibility of separating the PSN with TB from other family members to reduce the risk of spreading the disease, due to the family's reliance on shared cooking, washing and sanitary facilities.

The PSN’s of Elisabeth Dawut’s (top right) House hold, Opposite tank 58, Village 8, zone 2, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

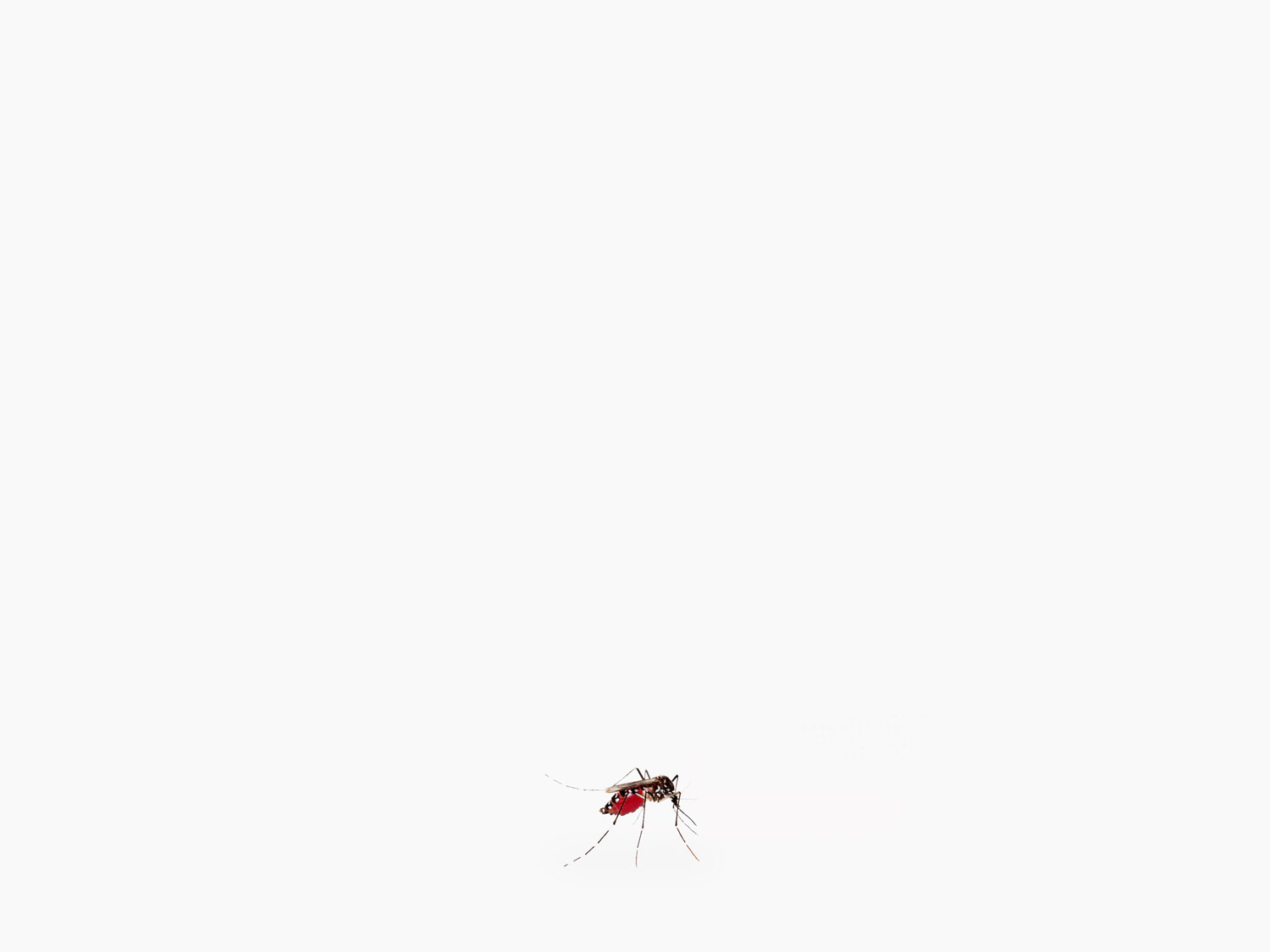

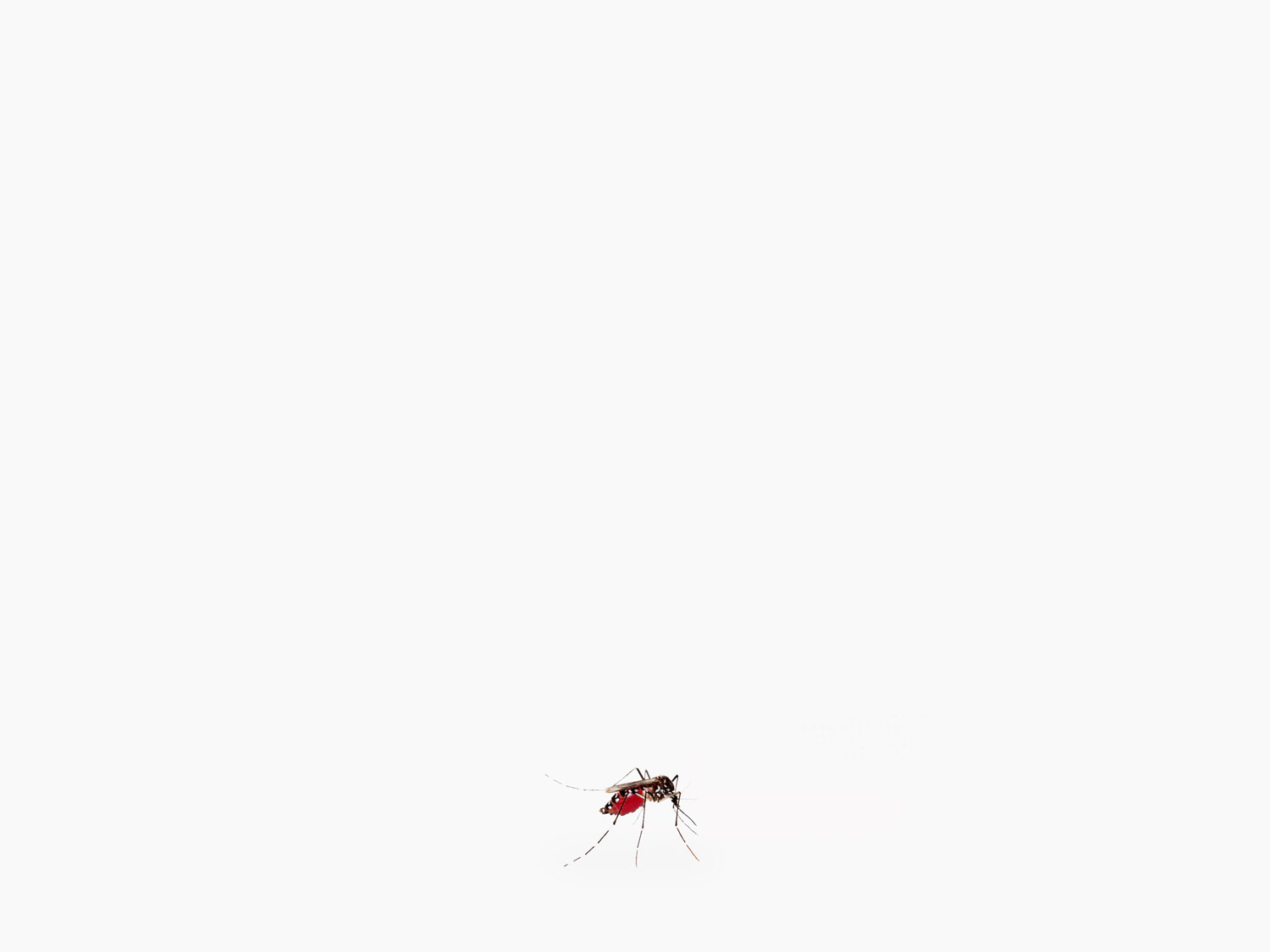

However, as the head clinician at Health Centre 3 in Zone 2 of Bidi Bidi indicated, malaria was the most prevalent disease at Bidi Bidi now that the refugee population was settled and had recovered from the malnutrition it sustained in South Sudan. Due to Uganda’s refugee settlements being situated in locations that promoted breeding sites for malaria and with climate change enhancing the transmission rate of the disease as unusually prolonged rains in the wet season gave mosquitoes more time to breed, Uganda's refugee population are at great risk of catching the disease.

Female Anopheles mosquito, appropriated image, location Unknown (2019)

According to Moses, The Chairman of The RWC of Cluster 2 of Bidi Bidi, most of the fatalities that happen in Bidi Bidi were due to malaria, but also due to delayed medical action or a lack of access to medication. Moses went on to explain how the child that was laid to rest here, in the burial ground of Zone 2 of Bidi Bidi, had died of malaria when their mother had failed to get any antimalarials from one of the health centres in the settlement.

The grave of a child that died of malaria, zone 2, Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement, Yumbe District (2017)

Although the development and aid agencies that supported South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda were committed to providing primary education, they were not always able to support secondary school pupils. As a result, the schooling of adolescent refugees was typically undertaken by existing secondary schools in nearby communities.

School desk, Itula Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

Large numbers of incoming refugee students put significant pressure on local schools and their respective staff as they tried to cater for many more students than they had space and resources to accommodate. Itula Secondary School (Itula SS), which is capable of hosting 7-800 students was twice over capacity as student numbers exceeded 1765. As a result, the schools classrooms became severely congested with up to 250 students squeezing into a single classroom.

Class at Itula SS, Itula Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

For the teachers that supported students at Itula SS, work was strenuous. Struggling to control the large numbers of students in temporary classrooms, that were noisy due to the lack of partitions between rooms, they found themselves straining their voices to reach to the back of large classes. After traveling long distances on foot to reach the school each morning and then teaching in hot temporary classrooms all day, they quickly became burnt out and in some cases left their posts for work else where.

_______Teacher at Itula SS, Itula Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

Although Itula SS was charging parents only 50,000UGX (£13.51 USD) per student a term to cover the running costs of the school, many household found it hard to pay. So where possible, students would attend for free, with parents exchanging skills instead of money to support the school.

So many extra students placed massive strain on the schools already poor infrastructure. With Itula's latrines having filled up before the summer, the head master Martin Okomo faced the prospect of having to delay the start of the school year because there was nowhere in the district of Moyo for the schools effluent to be taken.

Latrines, Ibakwe Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

With some students walking 4 hours each way to get to school, which meant leaving at 4.30am and returning at 8pm, and then in some cases going without lunch because they cannot afford it, those that attended secondary school did so because they were determined to progress in their lives even though they had been displaced.

_______ student of Itula Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

However, many adolescent refugees without the prospect of a secondary school education, faced being pressured by family members to return to South Sudan to undergo forcibly arranged marriages for a “bride price” or decided themselves to return to fight for the SPLM-IO rebels. Those that stayed in the refugee settlements without education were prone to damaging social behaviour such as alcoholism, drug abuse and petty criminal activity and the health risks of under-aged pregnancy.

However, though there were challenges, schools where doing what they could to provide for their eager students. At Idiwa secondary school (Idiwa SS) in zone two of Palorinya Refugee Settlement, a group of parents had mobilised to set up a secondary school to educate their children. Run by a staff of 18 unpaid South Sudanese teachers, the school’s classrooms had been constructed from material and monetary donations given by parents.

Class at Idiwa SS, Idiwa Parent Lead Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

Without enough classrooms to house every year group, lessons regularly took place under trees on the school’s grounds. With under tree lessons often being disrupted by rain and wind, students were keen for additional classrooms to be constructed so that lessons would not be curtailed by bad weather.

Without education, the headmaster of Idiwa SS said, “we cannot rebuild South Sudan, these young people are the leaders of tomorrow.” As a result of the parents commitment, the school has drawn the support of agencies such as Jesuit Refugee Services, the Windle Trust and the UNHCR, all of whom have all committed to providing additional infrastructure for the school.

Under-tree classroom at Idiwa SS, Idiwa Parent Lead Secondary School, Palorinya Refugee Settlement, Moyo (2017)

Through its Settlement Transformative Agenda, Uganda aims to enhance the development of the impoverished rural districts that host the counties refugee population. By placing refugee settlements in rural locations, Uganda intends to create economies where they had not existed before. This shop in Omugo Refugee Settlement, had been established by refugees within 3 days of their arrival, the proprietors hoping to capitalise on the lack of amenities in the newly settled area, which is far from the settlements main market.

Refugee run shop, Omugu, Refugee Settlement, Arua District (2017)

To encourage economic activities, refugee settlements would have allocated an designated area in which a central market could be developed. Markets typically contained all the shops that you might find in a small town, from fishmongers, to butchers, fruit and vegetable stalls, hair dressers, clothes shops and tailors, and even restaurants, nightclubs, currency exchanges, electronic stalls and general stores.

_____’s seamstress business, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

Fishmonger, Pagarinya refugee settlement, Amuru District (2017)

But regrettably there is a high failure rate amongst refugee businesses in settlements due to the lack of cash income earned by refugees, who instead rely on barter for goods and services, and the fact that refugee businesses are too far from host communities.

Failed refugee business, Pagarinya Refugee Settlement, Amuru District (2017)

Those that had benefited most from the policy were established businesses within the host community that sell their goods, often at an inflated price, to refugees. The unintended consequence of which was an increase in the price of goods sold to locals, as the demand created by refugees allowed local business owners to raise prices. As a result, impoverished locals, who were not receiving the rations or relief items that refugees did, suffered when development agencies did not additionally support vulnerable groups within the host community.

Phone shop, Adjumani, Amuru District (2017)

However, economic hardship is not just a problem faced by refugees and rural communities in Uganda. While 700,000 young people reach working age each year in Uganda, only 75,000 jobs are created each year, leaving 70% of Ugandans employed in agricultural work, most of whom work on a subsistence basis. Nevertheless, Uganda’s unwavering generosity to refugees continues in-spite of its own economic growth being minimal.

Total Petrol Station, Luwum Street, Kampala (2017)

With so few jobs going, rural urban migrants face the prospect of informal work at sites like Kampala’s Kiteezi municipal waste site, where waste pickers, the majority of whom are women, earn on average 100,000 UGX ($27 USD) a month.

Plastic sorted ready for recycling, Kiteezi municipal waste site, Kampala (2017)

_______, Kiteezi municipal waste site, Kampala (2017)

As rubbish arrives in the Kiteezi municipal waste site, waste pickers compete to collect all the paper, metals, and plastics that can be recycled from within each load. What recyclables that are found are then sold to the recycling companies, the majority of which are run by Chinese business men, that have been established next to the waste site. From there, the recyclables are transported in trucks returning to the international port in Dar es Salaam in Tanzania that had come to Uganda carrying cheap subsidised goods imported to Africa from China. From Dar es Salaam the recyclables will be shipped to China in the vessels that had brought the poor quality subsidised goods to Africa.

When working, waste pickers face multiple risks that are exaggerated by a lack of protective equipment and the competitive nature of their work which pays by the kilo and not by the hour. Risks include being crushed by heavy machinery, injuries caused by sharp objects, contracting HIV and other forms of viral infection from discarded medical waste, exposure to malaria and Dengue Fever due to the prevalence of mosquitos on sites like Kiteezi, poisoning by heavy metals and gastro-intestinal sicknesses like dysentery and cholera.

_______, Kiteezi municipal waste site, Kampala (2017)

Sorting out recyclables from newly dumped waste, Kiteezi municipal waste site, Kampala (2017)

Although, Uganda's economy is weak, refugee success stories are not uncommon. Having fled Rwanda due to political persecution, Angelica and her family had initially depended upon a small fruit stall in Kampala and her husbands work in construction to make ends meet. Now, having participated in a refugee entrepreneurship course at Jesuit Refugee Services (JRS) and having received a bursary to start a business, Angelica runs a small shop that sells cosmetics, beauty care items and her own handcrafted jewellery and hand bags.

Angelica, Angelica’s shop, Kampala, (2017)

____ and her three boys had fled to Uganda from the Democratic Republic of Congo following the politically motivated murder of her husband who had worked as a police chief in Goma. The killing took place early in the morning at their family home in front of _____ and her children. Before the men that had killed her husband could change their mind about letting her and the children go, _____ grabbed one item, a toasted sandwich maker, and fled. _____ explained, that even though there was no time to change out of her nighty, she knew that she had to bring the sandwich maker because it would provide for her family once they reached Kampala.

Toasted sandwich maker, Kampala (2017)

In a future where climate change is anticipated to induce more migration if emissions are left unchecked and finance for adaptation and loss and damage in developing countries is not forthcoming. Climate exacerbated conflict like South Sudan’s civil war, extreme weather events like hurricanes and slow onset climatic processes such as rising sea levels will create dangerous conditions and economic pressures that will leave climate vulnerable people, the majority of which will be in the Global South, with the agonising prospect of leaving their homes. As a result, anywhere between 25 million and 1 billion people worldwide are expected to be displaced by 2050.

Uganda’s out-standing emergency response to the crisis in South Sudan is a resounding example for nations in the Global North to aspire to. At a time when anti migration sentiment is on the rise in the Global North, Uganda offers us a lesson on how to treat refugees better in light of an uncertain future, where even if warming is limited to 1.5°C, increasing numbers of people, including those in the Global North, in countries such as the U.S., will be displaced by climate change.

“You never know when you too may become a refugee.”

Titus Jogo, Refugee Desk Officer at Office of the Prime Minister in Adjumani, 2017

As Titus Jogo, The Refugee Desk Officer for the Office of the Prime Minister in Adjumani, said to us during an interview in 2017: “The likes of Mr. Trump should be more generous to others because you never know, one day you too may become a refugee”. Yet as of 2020, 85% of the world's refugees continue to be hosted within developing regions, with nations like Uganda, Lebanon, Pakistan, Turkey, Colombia and Jordan hosting the largest numbers.

2.04 UGANDA: Possibly the best place to be a refugee in the world

Climate change is anticipated to displace between 25 million and 1 billion people worldwide by 2050. Learn how developing nations like Uganda host the majority of the worlds refugees and how their generosity is something for the rest of the world to aspire to.