2.02 BANGLADESH: Climate change expert

Bangladesh is arguably one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change, but that's just one part of the story.

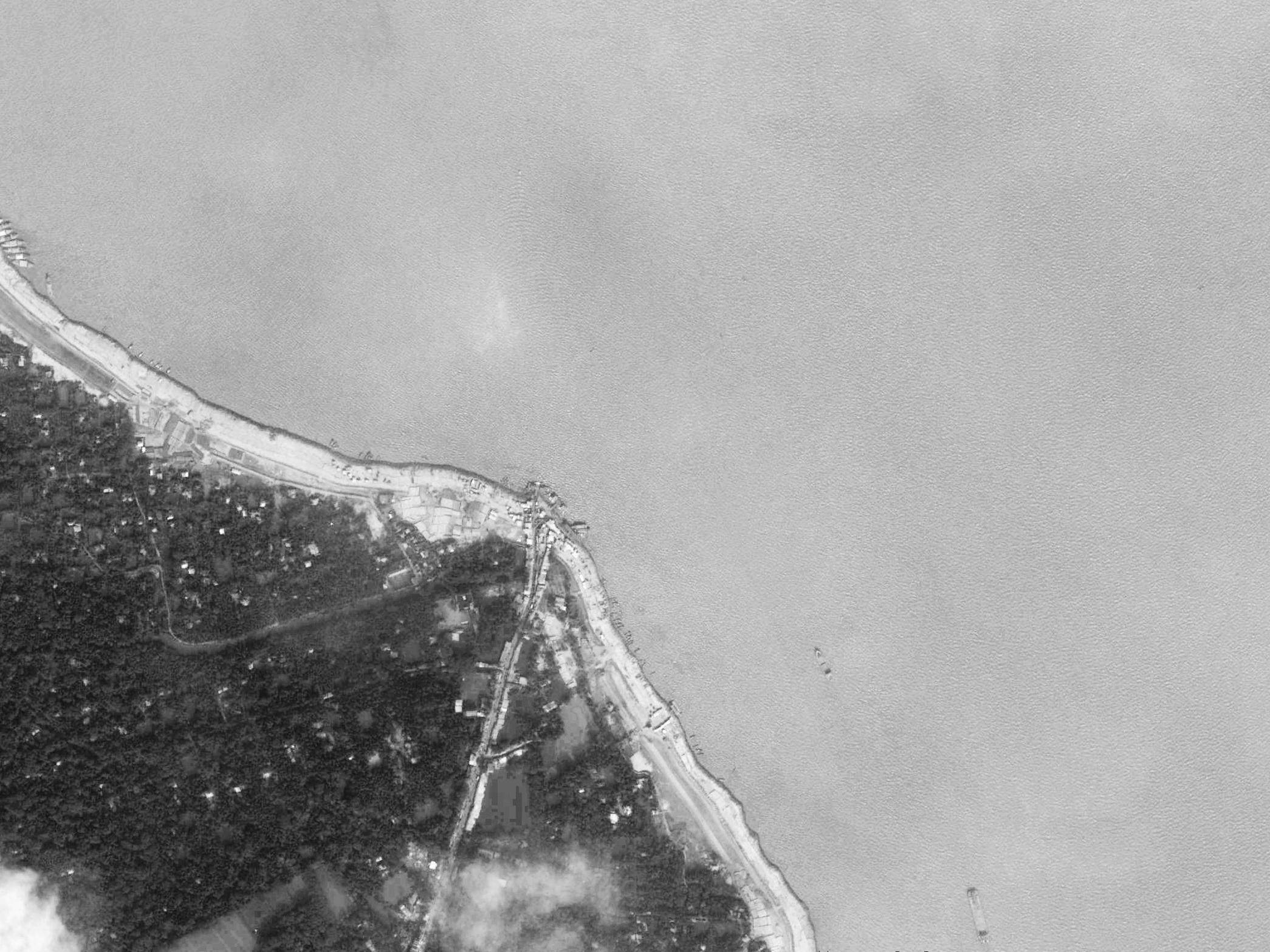

Building a coastal defence, Bhola Island, (2017)

With a population of over 160 million people in an area just over half the size of the United Kingdom the riverine nation of Bangladesh suffers regularly from catastrophic flooding, the impact of climate intensified cyclones, saltwater intrusion and even drought in its northern regions.

But that's just one part of the story. Although Bangladesh has come to be known as one of climate change's ground zeros it is in fact a climate change expert that offers leadership in the international climate change negotiation arena, as a domestic policy maker in disaster preparedness and locally led adaptation, through the deployment of nature based and low-tech solutions, indigenous technologies and through the resilience of its people.

But to understand why Bangladesh is a climate expert you need to first understand why it's vulnerable to climate change. To do that you need to look to low lying coastal areas in the south of the country, like Bhola Island where the coastlines have retreated as much as 5 kilometres in the last 10 years.

Elisha Ghat, Bhola Island, Image © 2020 Maxar Technologies and CNS / Airbus, Google Earth (2014 / 2019)

On the ground it looks like this, in 1984 this palm tree on the bank of the Meghna river would have stood 1 km away from the riverbank, but now its roots are submerged at high tide following the failure of the coastal defence that once protected it.

Lone palm, Daulatkhan, Bhola Island (2017)

With Bhola island's primary industry being fishing, those who depend on their catch for their livelihoods face enormous risks from tropical storms and cyclones when out at sea and at home in vulnerable coastal communities which are prone to coastal erosion and flooding.

______, Fisherman, Tula Tuli, Bhola Island, Bangladesh, (2017)

Fishing boats, Tula Tuli, Bhola island, Bangladesh, (2017)

As well as the risks they face from climate change, fishermen and women are also facing challenges related to increasingly depleted fish stocks as a result of pollution, overfishing and the adverse effects of harvesting shrimp fry for the shrimp farming industry which inadvertently sees juvenile fish caught and killed in the fine nets used to catch shrimp fry. As earnings from fishing falter, piracy has become so common that fishermen may have to pay dues to 2 or 3 different gangs of pirates to avoid being kidnapped or having their boats held to ransom.

______, river bank defence, Tula Tuli, Bhola Island, Bangladesh, (2017)

However in villages like Dalbanga South, where riverbank erosion, cyclones and saltwater intrusion have significantly impacted livelihoods, aquaculture is being used to cultivate fish and shrimp on land in small scale freshwater ponds and paddies that are now to salty to grow rice. By rearing fish for consumption in ponds, dwindling fish stocks are being protected and the livelihoods of those who can no longer fish economically and those whose land is now too salty to grow rice, or other crops are being diversified.

Fish pond, Dalbanga South, Barguna, Bangladesh, (2017)

.jpg)

_______, on a flood bank, Dalbanga South, Barguna, Bangladesh, (2017)

The village of Dalbanga South lies just east of the Sundarbans on the banks of the Bishkhali river. As sea level rise and melt water from the Himalayas have increase in the last 20 years, the river bank upon which the village sits has receded as much as one hundred meters in some places, leaving the village increasingly vulnerable to inundation when cyclones strike.

Riverbank erosion, Dalbanga South, Barguna, Bangladesh, (2017)

With the prospect of sea level rise drowning 18% of Bangladesh's landmass at the currently forecasted 3°C of warming, tens of millions of people are at risk of being displaced across the nation as riverbank erosion, saltwater intrusion and intensified cyclones force them from their land, deplete their financial resources and destroy their livelihoods.

Sunset over the Bishkhali river, Dalbanga South (2017)

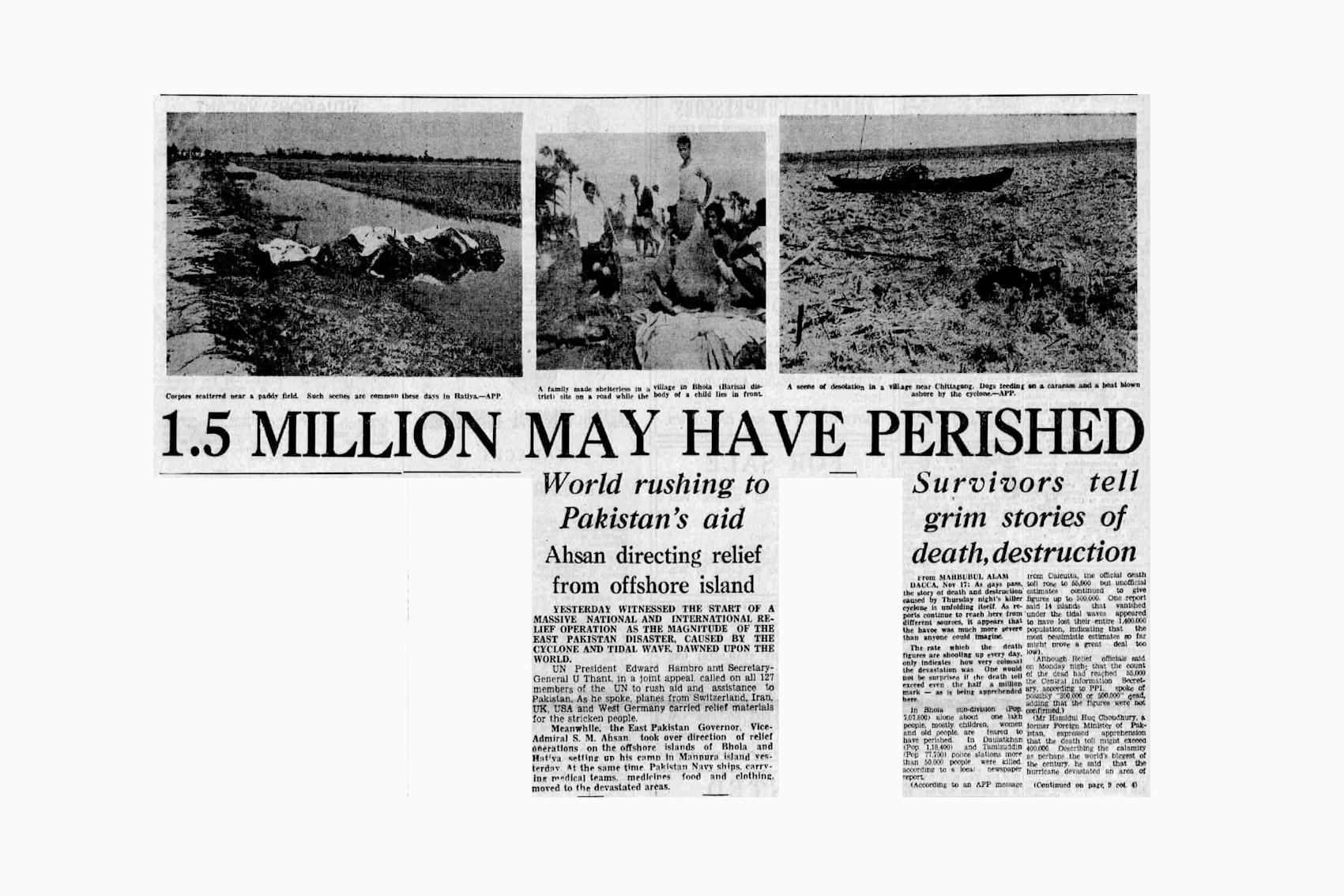

But Bangladesh is not sitting idle it is learning how to adapt to a challenging climatic future. When the Bhola cyclone struck Bangladesh in 1970 it is believed that as many as 500,000 people may have lost their lives as a 10m storm surge devastated offshore islands and wiped-out villages and crops on Bhola Island. But in the years since the storm, Bangladesh has taken major strides towards reducing the vulnerability of its people to cyclones. As of today, the country is at the forefront of disaster risk reduction and building coastal resilience in cyclone prone communities like Dalbanga South.

ITOS I satellite picture of Bhola cyclone near peak intensity, Nov. 12, (NOAA), 1970

Newspaper clipping reporting on the devastation caused by the Bhola cyclone (1970)

Dalbanga South was hit hard by category 5 Cyclone Sidr in 2007. When the storm hit, a number of the community lost family members and many lost cattle when the village was inundated by a 5-metre storm surge and battered by winds of up to 135mph. Since that time the community has participated in The International Centre For Climate Change and Development's (ICCCAD) GIBIKA capacity building workshops that provide training in disaster preparedness to reduce fatalities when cyclones do come.

Cyclone disaster preparedness courtyard meeting, Dalbanga South, Barguna, Bangladesh, (2017)

During the workshop, the participants, most of whom are women due to men prioritising work over attendance, learn about cyclone forecasting and alerts and how to prepare for, and organise the evacuation of their families and neighbours to cyclone shelters. Although women are the most likely to be killed or injured during a cyclonic event, due to their socially constructed roles that make it hard for them to leave their homes and livestock without permission of their husbands for fear of stigma, they play a pivotal role in the protection of their families when disasters strike.

Since the Bhola Cyclone of 1970 there have been some 2,500 cyclone and multipurpose shelters constructed along the 360-mile-long coast of Bangladesh. Often doubling as primary schools the shelters are equipped with rainwater capture and storage tanks, sanitary facilities, emergency rations and relief supplies. Due to the implementation of disaster preparedness workshops and the building of cyclone shelter-cum-schools in vulnerable communities, far fewer lives are now being lost when a cyclone does hit.

Tobgi School cyclone shelter, Bhola Island (2017)

Accommodating men and women in segregated wings with separate sanitary facilities the shelters are designed to reduce the prevalence of gender-based violence towards women during periods of extended refuge. Following research by Bangladeshi policymakers into the deaths of community members who had opted to stay to protect their livestock during cyclonic events, many shelters have now been updated to include additional refuges for cattle, sheep and goats.

Tobgi School cyclone shelter, Bhola Island (2017)

But nevertheless riverbank and coastal erosion is mounting pressure on rural communities as it eats up their land and their homes and affects their water supplies. As in the case of Barisal, where over the course of the 2016 monsoon rapid riverbank erosion irreversibly damaged the water treatment centre at Palashpur causing it to cease operation. The loss of the water treatment centre has exacerbated Barisal’s already existing water crisis that has been caused by reduced rainfall due to climate change and an increased demand for water as the towns size grows to accommodate rural urban migrants and those displaced by riverbank and costal erosion and cyclones.

Palashpur Water treatment plant, Barishal (2017)

Palashpur Water treatment plant, Barishal (2017)

For the community of Char Abdnani which is situated immediately behind the ruined facility, the threat of displacement is steadily growing as little has been done to protect the water treatment centre, something which they had hoped would inadvertently protect their homes.

_______, Char Abdnani, Barishal (2017)

________, Char Abdnani, Barishal (2017)

Already displacing more than 120,000 Bangladeshis a year, riverbank erosion can force affected families to move their homes every 2-3 years as the river encroaches on their doorsteps. Having relocated up to ten times, and subsequently lacking the financial capacity to buy new land or rebuild lost homes in their communities, many families make the difficult choice to migrate to large urban centres such as Dhaka to seek better prospects. But for those that cannot afford to migrate, they face the prospect of becoming stranded in temporary shelters in perilous locations such as on the side of government owned levies where they risk being displaced time and time again.

Palashpur Water treatment plant, Barishal (2017)

Palashpur Water treatment plant, Barishal (2017)

For those that have lost their agricultural land or livelihoods to riverbank erosion, there are few opportunities to earn a living in rural towns and villages apart from working as unskilled labourers carrying loads or in rural brick kilns like this one in Bainchotki. Such work is strenuous and poorly paid at 0.5-1 Taka (1-2¢ in USD) a load.

Bricks, which are the principal building material used in Bangladesh are moulded from clay rich soil or mud dug on land or dredged from rivers. The removal of soil which is often coercively purchased from impoverished farmers significantly contributes to the reduction in crop yields that climate change is already compounding in Bangladesh. While dredging for clay exacerbates riverbank erosion downstream and damages the aquatic ecosystem of rivers which further reduces fish stocks.

Workers loading and sorting sun dried bricks, Brick kiln, Bainchotki, Barguna (2017)

First moulded in wooden moulds and then sun-dried before being fired in coal-burning kilns, the bricks are carried by hand or in carts at every stage of the process. During the dry season in which brick makers are permitted to operate, this kiln in Bainchotki near Barguna, which is shaped like a double-walled zero with 3 segments, will be continuously firing bricks in one of its three sections whilst simultaneously loading and unloading in the other two sections.

Workers unloading fired bricks, Brick kiln, Bainchotki, Barguna (2017)

Once the bricks are stacked in the kiln with gaps between them to allow the heat to travel throughout the load, metal tubes with lids are positioned to allow the furnace to be fed with coal dust through out the firing and the top of the stack is covered in brick dust to stop heat escaping.

Sun dried bricks being stacked in the kiln ready for firing, Brick kiln, Bainchotki, Barguna (2017)

The bricks are then fired for 24 hours before being unloaded and then sorted into different grades. Kiln labourers work up-to 14 hours a day, day and night, seven days a week during the dry season to maximise the productivity of the kiln and their own incomes.

Opening the furnace to pour in coal dust, Brick kiln, Bainchotki, Barguna (2017)

Such physically demanding work often causes long term injuries to labourers, particularly the carrying of heavy loads on the head which can lead to the fusing of neck vertebrae in elderly porters which stops them from being able to turn their heads independently from their bodies. ____, a porter who was working to unload sand from a barge at Bagahat Ghat in Barisal explained that even though he could no longer move his head easily he had to continue labouring as he had no other means of generating an income.

______, a day labourer, Bagerhat Ghat, Palashpur, Barishal (2017)

However, Bangladesh is doing what it can to reduce riverbank erosion with what resources it can mobilise. In doing so it has developed a number of low-cost methods to slow down river bank erosion such as the deployment of sandbags and concrete blocks to absorb wave energy on coastlines and along riverbanks that are seeing rapid erosion.

Sandbags being laid for the foundation of a river bank defence, Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

To reduce the rate of riverbank erosion around the ferry launch at Elisha at the north-eastern tip of Bhola island, 10km of the riverbank is being reinforced. As the site manager of the project explained, the defence is first built flat on the ground inland of the river bank to allow it to gradually form a sloped bank as the river undermines the fore most part of the structure.

Sandbags being laid for the foundation of a river bank defence, Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017).

Site manager standing on a finished section of defence, Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

With Bhola Island’s principal economic activity being fishing and therefore much of the island's workforce either at sea or ill-suited to the strenuous nature of building riverbank defences, migrant workers from the north of Bangladesh, where heavy agricultural work is regularly undertaken, are enlisted to undertake the work. Carrying sandbags and concrete blocks that weigh up to 300kg, labourers work in teams of four and use bamboo poles to spread the weight between them.

While Bangladesh has developed innovative low-cost solutions to defend key sections of its coast line and river banks from erosion, it lacks the resources to defend the entirety of its 360 mile long coast line against an anticipated sea level rise of between 20cm and 2.5m if 3 degrees centigrade of warming were allowed to occur. A rise that would see up to as much as 18% of the countries land mass inundated.

_____, Day labourer, Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

For those that are displaced or who have lost their agricultural land to riverbank erosion, travelling to urban centres like Dhaka to work is regarded as the best way to improve their economic prospects. The Elisha Ferry Ghat, where this defence is being built is also the main transport hub for Bhola island that caters for the transportation of and foot passengers, fruit, vegetables and fish up the river to Dhaka and other regional centres.

_______,Waiting for the ferry to Dhaka, Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

When the Bhola cyclone struck in 1970 it displaced a large number of the island's residents, many of whom travelled to Dhaka and established informal communities which are still present today. Both those who were displaced in 1970 and those who reside on the island maintain a strong community network that supports temporary, cyclical and permanent migration to Dhaka from Bhola as well as profitable business links which make Bhola island one of the wealthiest regions outside of the urban centres of Dhaka and Sylhet.

Ferry passengers waiting next to concrete blocks drying in moulds, Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

With as many as 1200 rural urban migrants arriving in Dhaka every day from all over Bangladesh, for those who move to the city in search of work and better economic prospects migration is not seen as a curse, but instead as an adaptation strategy that helps them overcome economic hardships and periods of displacement. As a result, many Bangladeshi's undertake cyclical or seasonal migration to supplement their income even if they have not been displaced.

The Fahran-1 ferry loading in lieu of departing for Dhaka , Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

From Bhola to Dhaka the ferry takes 12-14 hours to journey upriver. Whilst onboard passengers claim a spot on the floor on which they will sleep, eat and rest throughout the journey. Those who are seasoned river travellers bring blankets, food and supplies for the journey to avoid the need to buy anything during the voyage at inflated prices.

The Fahran-1 ferry loading in lieu of departing for Dhaka , Elisha Ferry Ghat, Bhola Island (2017)

Dhaka’s ferry terminal at Saderghat on the Buriganga river is where most incoming rural-urban migrants first disembark as they reach the city. The bustling port in the centre of Dhaka's old town is where produce from all over the country is unloaded and is home to a fleet of small boats that ferry the cities residents across the river to the western side of the city.

Passenger ferry boats cross the Buriganga river, Saderghat, Dhaka (2017)

The water way which divides the city is characterised by its rank odour which is the result of the dumping of industrial effluent and raw sewage into the river from the cities overburdened drainage system. The rivers black colour is caused by the flushing of dye residues from clothing factories into the water.

Many of those arriving in Dhaka for work from rural locations will reside in slums, known locally as basti, the informal communities are home to more than 2 million people in urban centres across Bangladesh, of which 1.6 million are found in Dhaka in locations such as Kallyanpur Basti.

Kallyanpur Basti, Dhaka (2017)

Having left to avoid hazardous rural environments many migrants are exposed to many of the same hazards in Dhaka’s basti that they had left the countryside to avoid such as the dangers of flooding, poor sanitary conditions, accidental and intentional fires, heat stress and mosquito born illnesses.

_____ & _____ residents of Kallyanpur Basti, Kallyanpur Basti, Dhaka (2017)

Kallyanpur Basti which lies on the edge of a small lake that is gradually being filled by illegally dumped waste, is home to just over eight thousand people. Flooded by 1ft of water for most of the monsoon, residents face being continuously immersed in dirty water which leads to the development of skin conditions on their legs that can lead to infection.

The lake at the centre of Kallyanpur Basti, Kallyanpur Basti, Dhaka (2017)

To avoid getting wet at night when flooding occurs residents prop their beds up on bricks to raise them above the water level.

Bricks under a bed frame, Kallyanpur Basti, Dhaka (2017)

And it's not free or even cheap to live in a basti. When compared to the cost per square metre of renting a four-bedroom apartment in Dhaka, those living in basti are invariably paying more for a single room shack with no amenities, than those that can afford an apartment. Electricity and water prices and the cost of using a toilet are all dictated by the criminal gangs that provide the tenants with the illegally sourced connections, with fees often 6-10 times the price of what is paid for legal connections.

To pay their way most basti residents work within Dhaka’s informal economy in jobs such as portering with a basket or rickshaw riding to cover their rent, food and access to water, electricity and toilet facilities.

Rickshaw on the shore of Banani lake in Karail Basti, Dhaka (2017)

For those wishing to work as rickshaw riders who do not own their own bike it is necessary to rent one from a garage. Costing as much as 80TK (£0.73) a day in rent, riders make up-to 300Tk (£2.74) a day after rental costs are deducted.

Others find informal work in Dhaka's markets as porters, recycling market waste or selling produce which they have brought from whole sellers. Regular informal jobs in Dhaka often require contact or introduction to get and as a result are paid better. Basti that are made up of people that have migrated from the same rural community to Dhaka have strong social networks that support new arrivals by securing work for them, often before they arrive in Dhaka.

_____ & ______ recycling polythene from Karwan Bazar fish market, Tejgaon, Dhaka, (2017)

Carrying goods in rented baskets from the city’s large formal markets to the cities numerous smaller informal ones makes up the majority of the work of Dhaka’s porters. Working on a per load basis porters earn between 200-300TK (£1.83-2.74) per day after paying a rental fee of between 20-30TK (£0.18-0.27) rental fee for a basket. However at every opportunity within the chain of commerce surrounding the selling of market goods, middlemen extract a cut from those further down the supply chain than them. As a result those that work at the end of the chain like porters and small scale sellers earn very little and when there is no work to be done they risk going hungry.

______, a porter counting his money, Karwan Bazar, Tejgaon, Dhaka Bangladesh, (2017)

As Dhaka's population increases, space for living and working is becoming increasingly hard to find. So much so that active rail lines are being turned into informal markets and rail sidings into basti to cater for new arrivals and those who have no connection in more established communities.

______, a porter who’s arm was dislocated when carrying a heavy load, Karwan Bazar, Tejgaon, Dhaka Bangladesh, (2017)

Those that trade on the railway lines do so to avoid paying rates to the middlemen who control the formal markets by taxing small scale sellers for the right to sell on market grounds. Selling the lowest quality goods or those that have been collected as scraps and leftovers from formal markets, sellers must be on the lookout for trains to avoid being hit or having their produce destroyed.

Fish market left overs for sale, Karwan Bazar, Tejgaon, Dhaka Bangladesh, (2017)

Although trains blow their horns to warn those on the track of their imminent arrival, people get caught out when trains pass in opposite directions on both sides of the track at the same time. As many as 12 people had been killed at one time at train track markets like this one in Dhaka in recent years.

Those that reside in basti on rail sidings not only face the risk of living alongside an active train line but also the deafening noise of the trains as they pass within meters of where they sleep.

Rail side basti, Bijoy Swarani Flyover, Tejgaon, Dhaka (2017)

For the families who come to Dhaka, every member; including children can contribute to household earnings. Having migrated to Dhaka alone to live with his uncle who works at a lumber mill, 13-year-old _____ now works as an assistant at the same mill for 12 hours a day, 6 days a week. This sometimes-necessary evil of child labour as it is referred to by researchers in Bangladesh is leading schools and NGOs to schedule classes around the work of their pupils so that they may still take advantage of lessons and interventions such as youth clubs that allow working children to play and make friends after work.

_______, a 13 year old who works as an assistant at a lumber mill for 12 hours a day 6 days a week on his day off, Truck Stand Road, Tejgaon, Dhaka (2017)

For those who come to Dhaka without any resources or the support network that is required to find accommodation in one of Dhaka's basti, they face the prospect of living on the street or in parks like this one in Farmgate in temporary shelters. Sleeping under tarpaulin or polythene shelters that are erected against iron railings or shop fronts late at night and then dismantled at sunrise, Dhaka's so called floating population are found in the greatest numbers in streets near Sadarghat Dock, and on roadsides like Green Road in Raja Bazar.

Temporary shelter, Farmgate Park, Dhaka (2017)

Dhaka's so called floating population is diverse and includes families and individuals who have been displaced by riverbank erosion, flooding, cyclones and drought, economic migrants - some temporary and some permanent - as well as people affected by disabilities and injuries, orphaned children, adolescents and those addicted to drugs like Yaba which contains a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine. Often moving to Dhaka as a last resort without social networks or any financial means, individuals and families on the street scrape together just enough money to buy food at the end of each day by begging or working informal jobs that require no buy-in like collecting recyclables or the reselling of spoiled goods from the city’s wholesale vegetable and fish markets.

_______ Resident of Farmgate park who lost his arm when he fell of the roof of a moving train whilst he slept, Farmgate Park, Dhaka (2017)

With almost half of the population of Bangladesh living in poverty and increasing numbers of people being displaced by flooding, riverbank erosion and the economic impacts of climate change, migration towards urban centres is placing increasing strain on the nations already inadequate urban infrastructure.

Dhaka’s rapid unplanned growth has led to seemingly unending traffic jams within the capitals roads which are incapable of dealing with the number of vehicles that now ply the streets. Jams are responsible for wasting as much as 3.2 million working hours a day and draining billions of dollars from the city’s economy annually. With 500,000 people arriving from the countryside each year Dhaka is the world’s most densely settled megacity and one of its fastest growing.

Traffic jam, Dhaka - Mymensingh Highway, Tongi, Dhaka (2017)

However, rural-urban migration is also fuelling the labour requirements of the booming garment industry in Bangladesh which is now home to over 5 thousand garment factories where clothes are hand-stitched by low paid tailors. Though far less dangerous than much of the manual labour work that happens in Dhaka’s docks or brick kilns thousands of garment workers have been killed when poorly constructed factories have collapsed. When in 2013 the Rana Plaza clothing factory collapsed 1134 people were killed in less than 90 seconds. Although local laws have been put in place to regulate fire safety, pay and working conditions, enforcement is weak due to corruption and lack of inspections.

Tailors working within garment factories typically work 12 hours a day, 6 days a week and have daily targets of a thousand pieces to hit, that if not met will see their wages docked or hours extended. With factory managers prone to increasing targets without warning or when strikes about working conditions have decreased productivity, tailors find themselves mentally and physically exhausted at the end of each day.

Tailors in a garment workshop, Mirpur 1, Dhaka (2017)

Electronic’s and clothing market, Mirpur 1, Dhaka (2017)

With roughly 80% of Bangladesh's export earnings coming from the sale of clothing to global retails such as H&M, Primark, Walmart, Tesco and Aldi, there is pressure to keep the production of garments competitive so that retailers don't move production to other countries in the Global South. While wages are better than those earned by informal workers, they are still low with minimum wage set at 8,000TK (£73) a month for low skilled workers. With an average of 16,000TK (£142.20) needed a month to live comfortably in Dhaka workers are compelled to take on large amounts of overtime to supplement their earnings. Although garment workers in Bangladesh are paid less than any other in the world, wages earned continue to marginally elevate Bangladeshi’s out of poverty.

Although some of the jobs on offer in Dhaka are less physical than those on offer in the countryside, many jobs like working in Dhaka's numerous brick kilns put migrant workers at greater risk of injury or death than the cyclones or floods that they left the countryside to avoid. Dhaka’s Brick kilns offer seasonal work to rural-urban migrants, many of whom are temporary or seasonal migrants who work to substitute the income they derive from agriculture outside of harvest time with the intention of sending their children to higher quality schools in the countryside and better supporting their families.

Seasonal workers carrying fired bricks, brick kiln, Gabtoli, Dhaka (2017)

The kilns, which burn coal to generate the heat needed to fire bricks are the principal cause of the cities severe air pollution problem, releasing particulate matter, carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide amongst other pollutants. As legislation leads to the destruction of coal-burning kilns in and around Dhaka to reduce city-wide health problems such as respiratory, eye and skin diseases, gas-fired kilns with emissions of 50% less are taking their place.

Coal dust used to fuel the kiln, brick kiln, Gabtoli, Dhaka (2017)

Working long hours away from home, some temporary and seasonal migrants choose to live on-site in brick built temporary shelters to avoid paying for accommodation whilst in Dhaka so that they can maximise their income.

______ a Kiln worker, brick kiln, Gabtoli, Dhaka (2017)

Brick built shelter, brick kiln, Gabtoli, Dhaka (2017)

Each of Dhaka’s brick kilns will produce up to 1 million bricks a month during the 6 months in which they are permitted to operate by the government before closing for the monsoon, when many like this site in Gabtoli will be flooded.

Sun dried bricks damaged by flooding, brick kiln, Gabtoli, Dhaka (2017)

Other jobs, like working as porters offloading cement transported from factories outside of the city from barges onto trucks or into depots, expose labourers to health hazards. Dhaka’s rapid expansion has led to a real estate and building boom. Demand for bricks and cement has increased as the capital transitions from traditional low-rise to high-rise buildings as rural-urban migration and the demand for housing in the capital increases the price of land.

Porters unloading bags of cement under Gabtoli Bridge, Amin Bazar, Dhaka (2017)

Porters unloading bags of cement under Gabtoli Bridge, Amin Bazar, Dhaka (2017)

Although, many porters adapt makeshift cloaks and masks to reduce the amount of cement dust that comes into contact with their skin and is breathed in as they haul the bags of cement, skin, eye and lung diseases are common as cement dust is inhaled, blow into the eyes and as it sticks to sweaty skin.

______ a porter, taking a break from carrying cement, under Gabtoli Bridge, Amin Bazar, Dhaka (2017)

Earning between 1-2Tk per load porters will carry between 3-400 50kg bags a day in temperatures of close to 40 degrees centigrade risking severe dehydration and heatstroke, which can lead to death.

______ a porter, that has colapsed, under Gabtoli Bridge, Amin Bazar, Dhaka (2017)

Some jobs, like working in Dhaka's ship building yards or Chittagong's ship breaking yards can have fatal consequences for rural-urban migrants. In both cases labourers are exposed to hazards such as being crushed by heavy steel loads and poisoned by harmful contaminates such as crude oil residues or fuels which can also cause fires or explosions as ships are dismantled, constructed or refurbished.

Oil coated hand, ship building yard, Char Mirebagh, Dhaka (2017)

Work in Dhaka's ship building yards routinely exposes labourers to repetitive strain injuries and conditions such as tinnitus when preparing a ship's hull for painting, which involves repetitively striking the corroded metal hull of the ship with a hammer to remove the old paint. With little or no additional protective equipment other than gloves and welding goggles, workers rely upon cotton wool to protect their ears.

Welder, ship building yard, Char Mirebagh, Dhaka (2017)

As ships are dismantled in Chittagong's ship breaking yards, many of which are decommissioned oil tankers or cargo ships from international shipping companies such as Zodiac Maritime, large sections of the ship are cut with acetylene torches and then allowed to fall into the mud where they are then dismantled. But when sections are cut it is not always possible to know when or where they are going to fall and if everyone is clear, leading to workers being crushed or maimed by the failing steel or when they are flung from the ship as it is broken up.

_____, who is a dock worker with an acetylene cutter, ship building yard, Char Mirebagh, Dhaka (2017)

Working 12-14 hour shifts 6 days a week those working in Dhaka's ship building yards earn 340TK (£3.20) a day.

Angle grinder, ship building yard, Char Mirebagh, Dhaka (2017)

Although life in Dhaka is tough, many migrants are able to rise from the slums into higher quality accommodation, return to their hometowns or move to new communities and buy land to re-establish themselves such as those affected by the Bhola cyclone in 1970 who have gone on to buy land and form new communities in other less disaster prone areas of Bangladesh. But for many cyclical migrations will continue year upon year.

Barisal Ferry Ghat, Barisal (2017)

With most of those who migrate seasonally or temporarily doing so internally within Bangladesh, those that cross international boarders for work tend to be a minority because of the costs associated with getting a passport and flying. Of those who do work abroad, the majority are found within the Gulf States working in the construction, hospitality and oil industry’s. Although work is better paid and workers are able to send remittance home to their families in Bangladesh, migrant workers continue to face dangerous working environments and poor living conditions, and some find themselves trapped by employers that confiscate their passports or refuse to pay them.

______ a 14 year old boy who works 12-14 hours cleaning launch boats, Barisal Ferry Ghat, Barisal (2017)

Ultimately there is only so much that Bangladesh can adapt to, and a finite amount of loss and damage that the nation can endure without facing an existential crisis as the nations security and infrastructure falters. Furthermore, even if warming is capped at 1.5°C Bangladesh will still face significant challenges.

“It is already

too hot for us”

Sarder Shafiquel Alam

However, projects like this floating house prototype being undertaken at the Housing and Building Research Institute in Dhaka are indicative of Bangladesh’s refusal to be unprepared for a climate changed future. Floating houses which are normally made of low-cost materials that are accessible to low-income families are just one technology that have been adapted from indigenous knowledge to adapt to climate change. Other technologies include salt resistant rice strains for use in areas where cyclones have caused saltwater intrusion, vertical gardens, floating vegetable beds and micro irrigation that utilise used plastic bottles.

Floating house prototype, Kalyanpur, Dhaka (2017)

However, if leaders were to heed the lessons learned by Bangladesh about the way climate change is impacting the nation on the ground and the innovative solutions that they have developed to tackle it we may be able to avoid a future that is befouled with a great number of catastrophic climatic events and the displacement that they cause.

2.02 BANGLADESH: Climate change expert

Bangladesh is arguably one of the most vulnerable countries in the

world to climate change, but thats just one part of the story.

.jpg)